Introduction

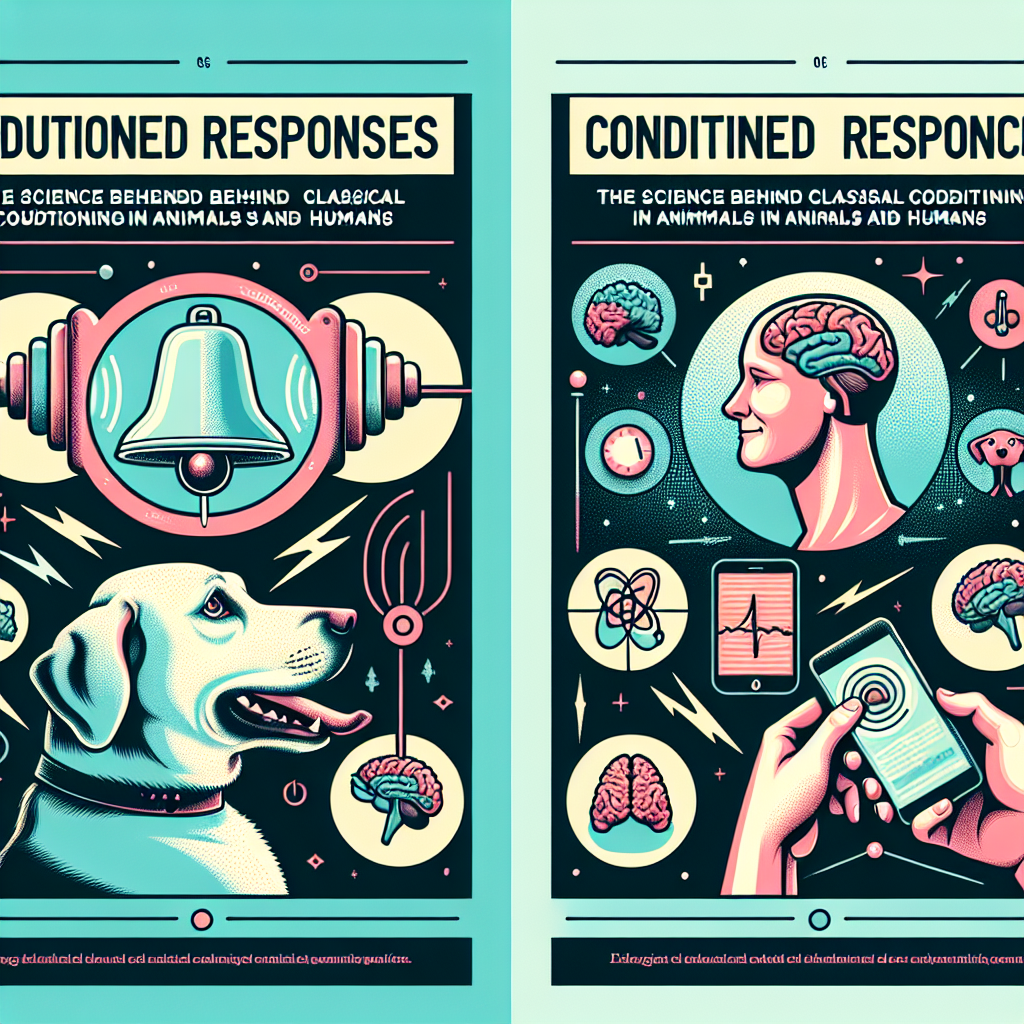

Imagine this: Every time a bell rings, your mouth starts watering, even if there’s no food in sight. This phenomenon is not merely a quirk of existence; it’s a powerful psychological principle known as classical conditioning. The study of conditioned responses—specifically, the science behind classical conditioning in animals and humans—offers insight into behavior modification, learning processes, and even therapy contexts. This article will explore the intricate dance between stimuli and responses, revealing the underpinnings of conditioned responses in never-before-seen depth.

What Is Classical Conditioning?

Classical conditioning is a fundamental learning process first explored by Ivan Pavlov, a Russian physiologist. In his now-famous experiment, Pavlov observed that dogs would salivate not just at the sight of food, but also at the sound of a bell that had been paired with food presentations. This leads us to the cornerstone of conditioned responses: a natural reflex gets triggered by an associated stimulus.

Key Terminology

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Unconditioned Stimulus (US) | A stimulus that naturally evokes a response (e.g., food). |

| Unconditioned Response (UR) | The natural reaction to the unconditioned stimulus (e.g., salivation). |

| Conditioned Stimulus (CS) | A previously neutral stimulus that, after association, triggers a conditioned response (e.g., a bell). |

| Conditioned Response (CR) | The learned response to the conditioned stimulus (e.g., salivation in response to a bell). |

The Mechanisms Behind Conditioned Responses

Conditioned responses stem from associative learning—where individuals link a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned one. The brain’s neural pathways become altered through repetitions, leading to conditioned responses. Let’s take a closer look at the steps involved:

- Acquisition: The initial learning of the relationship between the unconditioned and conditioned stimuli.

- Extinction: Over time, if the conditioned stimulus is presented without the unconditioned stimulus, the association weakens, leading to diminished responses.

- Spontaneous Recovery: After extinction, a previously conditioned response can still reappear after a pause when the conditioned stimulus is presented again.

Case Study: Pavlov’s Dogs

Pavlov’s experiments consisted of ringing a bell before presenting food. Gradually, the dogs learned to associate the bell (conditioned stimulus) with food (unconditioned stimulus), resulting in salivation (conditioned response) at the sound of the bell alone. This experiment serves as a perfect example of the mechanism behind conditioned responses.

Analysis of Relevance

Pavlov’s work laid the groundwork for behavioral psychology, demonstrating how emotions and behaviors can be learned and unlearned, influencing everything from education to therapeutic practices today.

Real-World Applications of Conditioned Responses

Conditioned responses extend beyond laboratory settings and into ordinary life and various fields, including education, animal training, treatment of phobias, and more.

In Education

In a classroom, teachers often use positive and negative reinforcements—akin to classical conditioning. For example, a student might receive praise (unconditioned stimulus) for completing a task (unconditioned response). Over time, the praise becomes a conditioned stimulus that motivates the student (conditioned response) to work harder.

Animal Training

Animal trainers frequently utilize conditioned responses to instill specific behaviors. For example, a trainer might use a clicker (conditioned stimulus) alongside a treat (unconditioned stimulus) to teach a dog tricks. Over time, the dog learns to associate the click sound with the_positive experience of receiving a reward.

Table: Comparison of Training Methods

| Method | Example | Conditioned Response |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Conditioning | Clicker training | Dog sits upon hearing the click |

| Operant Conditioning | Positive reinforcement with treats | Dog performs a trick for a treat |

| Negative Reinforcement | Removal of an uncomfortable stimulus | Dog stops barking when commanded |

Therapeutic Applications

Classical conditioning principles are prevalent in addressing phobias and anxiety disorders. Desensitization techniques utilize conditioned responses, allowing individuals to face fears gradually in safe environments.

Case Study: Little Albert

In a controversial study conducted by John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner, a child named Albert was conditioned to fear a white rat through repeated exposure to loud, frightening noises (unconditioned stimulus). The once-neutral rat became a conditioned stimulus, leading to a conditioned response of fear.

Analysis of Relevance

This case study raised ethical concerns, yet it provided insight into how fears and anxieties are acquired—demonstrating the power of classical conditioning in shaping behavior.

Conditioned Responses in Daily Life

Conditioned responses manifest in various daily experiences. Have you ever felt a surge of nostalgia at the sound of an old song? This is classical conditioning in action. Let’s explore additional examples:

Advertising and Marketing

Marketers often use conditioned responses to evoke emotional reactions that drive consumer behavior. A jingle (conditioned stimulus) paired with comforting memories (unconditioned stimulus) can prompt a positive reaction (conditioned response) toward a brand.

Social Conditioning

Social behaviors may also be conditioned through reinforcements or punishments. For example, a child may learn to say "please" and "thank you" due to positive feedback from adults, leading to a conditioned response to seek approval.

Health and Conditioning

Behavioral therapies to counteract unhealthy habits also highlight conditioned responses. For instance, an individual may associate unhealthy snacks with feelings of comfort (unconditioned stimulus), requiring structured interventions to unlearn these responses.

Conclusion

Conditioned responses are interwoven into the fabric of our lives, shaping our behaviors, emotions, and interactions with the world. Understanding the science behind classical conditioning in animals and humans provides invaluable insights not only into psychology but also into the complexities of life itself. By harnessing these principles, we can modify maladaptive behaviors, enhance learning, and even cultivate healthier relationships with ourselves and others.

Actionable Insights

As you navigate your daily life, consider the principles of conditioned responses. Are there behaviors you’d like to reinforce or unlearn? By being aware of the stimuli around you and their accompanying responses, you can take active steps toward positive change.

FAQs

1. What is the significance of classical conditioning?

Classical conditioning is central to understanding how behaviors and emotions are learned, providing insights for education, animal training, and therapeutic interventions.

2. Can conditioned responses be unlearned?

Yes, through a process called extinction, conditioned responses can weaken and fade over time, particularly if the conditioned stimulus is presented without the unconditioned stimulus.

3. How does classical conditioning differ from operant conditioning?

Classical conditioning involves learning through associations between stimuli, while operant conditioning focuses on learning through the consequences of behavior (rewards or punishments).

4. Are conditioned responses observable in humans?

Absolutely! We exhibit conditioned responses in various situations, from social interactions to ingrained habits and even emotional reactions to specific cues.

5. How can I utilize classical conditioning in everyday life?

You can apply classical conditioning principles to promote positive behaviors by associating desired actions with rewarding stimuli, using reinforcement in educational or therapeutic contexts.

This in-depth exploration of conditioned responses showcases how foundational principles of classical conditioning underpin a vast array of behaviors, making it essential knowledge for anyone interested in psychology, education, animal training, or personal growth.